BETULKAN RUMAH SENDIRI YANG NAK ROBOH TU !!! Jangan Masuk Campur Hal Ehwal Keselamatan Negara !!!!Tajuk Isu : PAKATAN HARAM TUBUH MPKR, BIDAS CARA KERAJAAN KENDALIKAN ISU KESELAMATAN DI SABAH ??

A. Statement salah seorang blogger seperti di bawah :-

CONCLUSIONS OF

SECRETARY-GENERAL

In submitting his own conclusions, the Secretary-General said he had given consideration

to the circumstances in which the proposals for

the Federation of Malaysia had been developed

and discussed, and the possibility that people

progressing through the stages of self-government might be less able to consider in an entirely free context the implications of such

changes in their status than a society which

had already experienced full self-government

and determination of its own affairs. He had

also been aware, he said, that the peoples of

the territories concerned were still striving for

a more adequate level of educational development. Taking into account the framework within which the Mission's task had been performed,

he had come to the conclusion that the majority of the peoples of Sabah (North Borneo)

and of Sarawak had given serious and thoughtful consideration to their future and to the

implications for them of participation in a Federation of Malaysia. He believed that the majority of them had concluded that they wished

to bring their dependent status to an end and

to realize their independence through freely

chosen association with other peoples in their

region with whom they felt ties of ethnic association, heritage, language, religion, culture,

economic relationship, and ideals and objectives. Not all of those considerations were present in equal weight in all minds, but it was

his conclusion that the majority of the peoples

of the two territories wished to engage, with

the peoples of the Federation of Malaya and

Singapore, in an enlarged Federation of Malaysia through which they could strive together

to realize the fulfilment of their destiny.

The Secretary-General referred to the fundamental agreement of the three participating

ASIA AND THE FAR EAST 43

Governments and the statement by the Republic

of Indonesia and the Republic of the Philippines

that they would welcome the formation of the

Federation of Malaysia provided that the support of the people of the territories was ascertained by him, and that, in his opinion, complete compliance with the principle of selfdetermination within the requirements of General Assembly resolution 1541(XV), Principle

IX of the Annex, had been ensured. He had

reached the conclusion, based on the findings

of the Mission that on both of those counts

there was no doubt about the wishes of a sizeable majority of the people of those territories

to join in the Federation of Malaysia

.

SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS

The Federation of Malaysia was proclaimed

on 16 September 1963. On 17 September, at

the opening meeting of the General Assembly's

eighteenth session, the representative of Indonesia took exception to the fact that the seat of

the Federation of Malaya in the Assembly Hall

was being occupied by the representative of the

Federation of Malaysia. Indonesia had withheld recognition of the Federation of Malaysia

for very serious reasons and reserved the right

to clarify its position on the question of Malaysia at a later stage

Recognition of Malaysia was also withheld by

the Republic of the Philippines. During the

general debate at the eighteenth session, both

Indonesia and the Philippines expressed their

reservations about the findings of the United

Nations Malaysia Mission. The representatives

of the United Kingdom and of the Federation

of Malaysia replied to the Indonesian and Philippine charges and upheld the findings of the

United Nations Malaysian Mission

A. Statement salah seorang blogger seperti di bawah :-

B. STATEMENT DAN LIPUTAN PENUBUHAN MPKR PAKATAN HARAM BERKENAAN KESELAMATAN NEGARA DAN KEJADIAN PENCEROBOHAN DI LAHAD DATU : -

KOMEN ADMIN BLOG ABG :-

KOMEN ADMIN BLOG ABG :-

KRONOLOGI TRAGEDI PENCEROBOHAN DI LAHAD DATU, SABAH, MALAYSIA - PENJELASAN DAN SEJARAH.

QUESTIONS CONCERNING ASIA AND THE FAR EAST 41

THE QUESTION OF MALAYSIA

EXCHANGE OF CORRESPONDENCE

The proposal for the formation of Malaysia

was first made by the Prime Minister of the

Federation of Malaya in May 1961, and a

Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee

was established at a regional meeting of the

Commonwealth Parliamentary Association in

July of the same year. Following a report by a

Commission of Enquiry (the Cobbold Commission), which had conducted meetings in

Sarawak and North Borneo from February to

April 1962, the Governments of the United

Kingdom and the Federation of Malaya issued a joint statement, on 1 August 1962, that

in principle the Federation of Malaysia should

be established by 31 August 1963. A formal

agreement was prepared and signed in London

on 9 July 1963 on behalf of the Governments

concerned (the Federation of Malaya, North

Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore).

On 5 August 1963, following a six-day meeting in Manila of the Heads of Government of

the Federation of Malaya, Indonesia and the

Philippines, the Foreign Ministers of these three

States cabled the Secretary-General of the

United Nations, requesting him to send working teams to Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak in order to ascertain the wishes of these

peoples with respect to the proposed Federation. The three Governments would similarly

send observers to the two territories to witness

the investigations of the working teams and the

Federation of Malaya would do its best to ensure the co-operation of the British Government and of the Governments of Sabah and

Sarawak.

The terms of reference of the request to the

Secretary-General were set out in paragraph 4

of the Manila Joint Statement as quoted in the

request addressed to the Secretary-General by

the three Foreign Ministers:

The Secretary-General or his representative should

ascertain, prior to the establishment of the Federation

of Malaysia, the wishes of the people of Sabah

(North Borneo) and Sarawak within the context of

General Assembly resolution 1541(XV), Principle IX

of the Annex, by a fresh approach, which in the

opinion of the Secretary-General is necessary to ensure complete compliance with the principle of selfdetermination within the requirements embodied in

Principle IX, taking into consideration: (1) The

recent elections in Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak but nevertheless further examining, verifying

and satisfying himself as to whether: (a) Malaysia

was a major issue if not the major issue; (b) electoral

registers were properly compiled; (c) elections were

free and there was no coercion; and (d) votes were

properly polled and properly counted; and (2) the

wishes of those who, being qualified to vote, would

have exercised their right of self-determination in the

recent elections had it not been for their detention

for political activities, imprisonment for political offences or absence from Sabah (North Borneo) or

Sarawak.

(Principle IX of the Annex of General Assembly resolution 1541(XV) of 15 December

1960 provided that a non-self-governing territory integrating with an independent State

should have attained an advanced stage of selfgovernment with free political institutions. The

same principle lays down that integration should

be the result of the freely expressed wishes of

the territory's peoples, expressed through informed and democratic processes, impartially

conducted and based on universal adult suffrage.1

)

In his reply to the three Foreign Ministers

on 8 August, the Secretary-General made it

clear that he could undertake the task proposed

only with the consent of the United Kingdom.

He believed that the task could be carried out

by his representative and proposed to set up two

working teams—one to work in Sarawak and the

other in Borneo—under the over-all supervision

of his representative. The Secretary-General

emphasized that the working teams would be

responsible directly and exclusively to him and,

on the completion of their task, would report

through his representative to the SecretaryGeneral himself who, on the basis of this report, would communicate his final conclusions

to the three Governments and the Government

of the United Kingdom. It was the SecretaryGeneral's understanding that neither the report

of his representative nor his conclusions would

be subject in any way to ratification or confirmation by any of the Governments concerned.

1

See Y.U.N., 1960, pp. 509-10.42 POLITICAL AND SECURITY QUESTIONS

REPORT OF

UNITED NATIONS MISSION

On 12 August, the Secretary-General announced the assignment of eight members of the

Secretariat, headed by Laurence V. Michelmore as his representative, to serve on the

United Nations Malaysia Mission. The Mission left New York on 13 August 1963 and arrived in Kuching, Sarawak, at noon on 16

August.

The Mission was divided into two

teams, each comprising four officers, one to

remain in Sarawak and the other to work in

Sabah (North Borneo). Both teams remained

until 5 September. Observers from the Federation of Malaya and the United Kingdom were

present throughout all of the hearings conducted by the Mission. Observers from the Republic of Indonesia and from the Philippines

arrived only on 1 September and attended

hearings in the two territories on 2, 3 and 4

September.

On 14 September, the final conclusions of

the Secretary-General with regard to Malaysia

were made public. These conclusions were based

upon a report submitted to the Secretary-General by the Mission. This report stated that it

had been understood that by the "fresh approach" mentioned in the terms of reference

established in the request to the Secretary-General, a referendum, or plebiscite, was not contemplated. The Mission had considered that it

would be meaningful to make a "fresh approach" by arranging consultations with the

population through elected representatives, leaders and the representatives of political parties

as well as non-political groups, and with any

other persons showing interest in setting forth

their views. During the Mission's visits to various parts of the two territories, it had been

possible to consult with almost all of the "grass

roots" elected representatives. Consultations

were also held with national and local representatives of each of the major political groups

and with national and local representatives of

ethnic, religious, social and other groups, as

well as organizations of businessmen, employers and workers in various communities and

social groups.

As far as the specific questions which the

Secretary-General was asked to take into consideration were concerned, the members of the

Mission concluded, after evaluating the evidence available to them, that: (a) in the recent elections Malaysia was a major issue

throughout both territories and the vast majority of the electorate understood the significance

of this; (b) electoral registers were properly

compiled; (c) the elections were freely and impartially conducted with active and vigorous

campaigning by groups advocating divergent

courses of action; and (d) the votes were properly polled and counted; the number of instances where irregularities were alleged seemed

within the normal expectancy of well-ordered

elections.

The Mission came to the conclusion that the

number of persons of voting age detained for

political offences or absent from the territories

when voting took place was not sufficient to

have affected the result.

The Mission also gave careful thought to the

reference in the request to the Secretary-General that "he ascertain prior to the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia the wishes

of the people of Sabah (North Borneo) and

Sarawak within the context of General Assembly resolution 1541 (XV), Principle IX of the

Annex." After considering the constitutional,

electoral and legislative arrangements in Sarawak and Sabah (North Borneo), the Mission

came to the conclusion that the territories had

"attained an advanced stage of self-government

with free political institutions so that its people

would have the capacity to make a responsible

choice through informed democratic processes."

Self-government had been further advanced in

both territories by the declaration of the respective Governors that, as from 31 August

1963, they would accept unreservedly and automatically the advice of the respective Chief

Ministers on all matters within the competence

of the State and for which portfolios had been

allocated to Ministers. The Mission was further of the opinion that the participation of the

two territories in the proposed Federation, having been approved by their legislative bodies,

as well as by a large majority of the people

through free and impartially conducted elections in which the question of Malaysia was a

major issue and fully appreciated as such by

the electorate, could be regarded as the "result

of the freely expressed wishes of the territory'sQUESTIONS CONCERNING

peoples acting with full knowledge of the

change in their status, their wishes having been

expressed through informed and democratic

processes, impartially conducted and based on

universal adult suffrage."

1) Berkenaan peristiwa Pencerobohan di Lahad Datu oleh pengganas 'Tentera Kesultanan Sulu', sebagaimana yang dijelaskan seperti di atas sebenarnya adalah suatu 'Provokasi Musuh' terutama 'komplot' daripada Kumpulan 'Sultan Kiram' dan Nur Misuari serta 'nasi tambah dan campurtangan' pihak ketiga berupa tangan tangan ghaib daripada Malaysia sendiri yang telah berlarutan setelah sekian lama sejak Perjanjian Bilateral di antara 3 pihak iaitu Kerajaan Filipina, Malaysia dan Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) pada 7hb. Oktober, 2012. Keterangan seperti link di bawah ini : -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moro_Islamic_Liberation_Front , iaitu suatu perjanjian damai yang bermula suatu penyatuan Bangsamoro serta pendamaian dengan kerajaan Filipina yang diinisiatifkan oleh kerajaan Malaysia yang diterajui oleh YAB Perdana Menteri Dato' Sri Mohd Najib Tun Razak.

Rujukan 1 :

2. KESULTANAN SULU - SEJARAH DAN LATAR BELAKANGNYA - PART 1

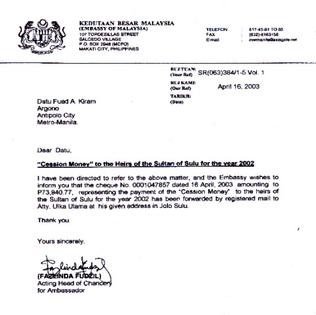

Rujukan 2 : - Surat rasmi terakhir dari Kerajaan Malaysia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Malaysian_Lease_Payment_for_Sabah_for_2003.jpg

|

| Contoh Surat dari Kedutaan Malaysia di Manila, Filipina kepada Sultan Sulu ketika itu, yang menyatakan bayaran 'Cession'tersebut adalah hanya wang saguhati Kerajaan Malaysia kepada Sultan Sulu yang juga berupa bayaran terakhir kepada pihak berkenaan. |

Rujukan 3 :- Hieraki Kesultanan Sulu

DATA RASMI SULTAN SULU

| |

| Country | Sultanate of Sulu |

|---|---|

| Titles | Sultan of Sulu |

| Founder | Sultan Jamalul Kiram I |

| Current head | Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram of Sulu |

| Founding | 1823 |

BENDERA RASMI KESULTANAN SULU

3. PENDIRIAN KERAJAAN FILIPINA

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Implementation_of_the_Manila_Accord.djvu

4. SULTAN KESULTANAN SULU YANG DIIKTIRAF OLEH KERAJAAN FILIPINA.

http://www.royalsultanateofsulu.org/#!sultan-of-sulu

SEJARAH KESULTANAN SULU :-

The Kingdom of Sulu – its equally correct but more precise name being the Royal Sultanate of Sulu – is a traditional Islamic monarchy of the Tausug people; a nation, both historical and extant, which currently continues its existence under the supreme authority of the Republic of the Philippines. Among the princes and chiefs of the Filipino first nations, the Sovereigns of Sulu are considered as the premier traditional monarchs; and their royal dignity and the style of Majesty, uncommon for the Malay sultans, is indisputably recognized for centuries.

Apart of the island of the same name, the Sultanate’s territory includes various islands and districts in and around the Sulu Sea. The Sultan-King enjoys also the supreme sovereign rights for the north of Borneo, which province is currently lent by Malaysia and administered as the state of Sabah.

I. The realm’s pre-history

The legend – realistic, largely supported by evidences, and mostly reliable – tells that the Sultanate’s immediate predecessor, Raja Baginda, a relatively peaceful conqueror from Sumatra, introduced many novelties in Sulu in 1390-ies, including the centralised power of a supreme monarch, the elephants, and – most significantly – the Sunnite Islam. Shortly prior to Baginda’s arrival, Islam was preached in the region by the great missionary, Karim-ul Makdum, but the heathen (probably Hinduist) customs and rituals of the local communities were generally maintained until the Raja embraced the monotheism. Baginda had no male heir and his dominion became a dowry of his daughter, Princess (Dayang-Dayang) Paramisuli. It is believed that Paramisuli’s mother was herself a heiress to a prominent local chief.

II. The Hashemite dynasty

The man who married Paramisuli was Sayyid Abu Bakr Abirin, a nobleman, a lawyer and a theologian. As his title of Sayyid suggests, he belonged to the direct posterity of Prophet Mohammad, namely of its Hashemite branch. A son of a Mecca-born Arab father (and, according to some authors, of a Malay princess), Abu Bakr was raised in Johore, being no stranger to the East Indian region. Baginda appointed Abu Bakr as his heir and made him a chief judge in matters temporal and spiritual.

On his accession, Abu Bakr was able not only to maintain the centralized power achieved by father-in-law, but to develop it considerably, and to establish a Sultanate – a theocratic monarchy in which he was a sacred ruler, both a sovereign and a religious leader, a “Paduka Mahasari Maulana al-Sultan Sharif-ul-Hāshim”. This occurred in 1457. Since then, the Sultanate of Sulu remains a joint entity, temporal and spiritual alike, which phenomenon is actually well-known to the Christian Europe, and sometimes defined as persona mixta. Among Abu Bakr’s temporal reforms, the territorial repartition is particularly telling of his power: it divided the island into five districts and included all the sea-shore as well as the vast territory around the residence into the immediate domain of the Sultan. The Sultanate extended its influence far away the shores of the island of Sulu and became a mighty maritime power. Its power and influence was effective on short and long distances, as it was wittily illustrated by the later Sulu badge, a kris and a spear.

It was already under Abu Bakr’s sons, Sultan Kamal ud-Din and Ala ud-Din, that the Tausugs faced the European expansion, but for long they were able to oppose it. From time to time, the Europeans invaded the territory of the Sultanate and even the capital city of Jolo was captured several times, but the Tausug state persisted. It seemed for a while that the Jesuit missionaries succeeded in Sulu; Sultan Alim ud-Din was benevolent to them and even was baptised in 1750, becoming King Ferdinand I of Sulu. However he faced both opposition of his relatives and compatriots and, more decisively, the attitude of the Spanish commanders by whom he was detained and imprisoned shortly afterwards. When the Sultan regained the freedom and the throne (with the assistance of English troops), he preferred to act henceforth as the jihad-performing “Amir ul-Muminin” (the Lord of the [Mohammedan] Faithful) and today is famous among the Tausugs under that name.

Both Ali mud-Din and his son Sultan Israel faced growing instability within the Sultanate and within the Royal House, dramatically provoked by exterior pressure. Since their reigns, the traditional line of succession was interrupted several times, for political reasons, by various “anti-Sultans” (members of the dynasty’s younger branches or even of related families), but at the same time these deviations helped to regularise the dynastical doctrine and to make the lawful inheritance of the throne more linear.

Sultan Jamal ul-Kiram (died in 1844) was the first to use the name “Kiram”; his posterity became the Royal branch of the Sulu Hashemites, the Sovereign House as such, and from him descended all the posterior legitimate Sultans.

It worth mentioning that this Sultan was the first known historian of his nation; he collected various legends and tales, reliable and rather fantastic alike, and dictated this unique compilation to his councillor.

III. The vassal status

Due to the wars and the conquests, the regional and inter-regional trade routes changed radically, diminishing considerably the Sultanate’s former importance. The ports controlled by the European, the use of steamboats and the continuous warfare deprived the fleet and the harbours of the Tausugs of their former importance; as a result, for a while most of the Tausug maritime energy was accumulated by the local piracy rather than by the regular trade. In 1851, after a successful raid of General Urbiztondo, Sultan Mohammad Pulalun was forced to sign a pact which turned the Sultanate into a vassal autonomous state, incorporated into the Spanish monarchy. In accordance to the Spanish text of the pact, the Sultan ceded his sovereign rights to Spain; the Tausug text was much more moderate and merely acknowledged the supreme sovereignty of Spain, leaving the Sultan’s exclusive prerogatives intact. One has to admit that de facto the later model was followed. The tension continued and the Spanish occupied, after a dramatic siege and battle, the Sultanate’s capital Jolo in 1876, but even this did not terminate – either de facto or de jure – the vast autonomy of the Kingdom-Sultanate.

Then Spain transferred its rights and claims to the USA, and the bilingual trick from 1851 was repeated, intendedly or not, by the American representatives when the Bates Agreement was signed by Sultan Jamal ul-Kiram II. This agreement was, however, unilaterally abrogated by the USA, leaving the Sultan (despite of his protests) free both of guarantees and of obligations imposed by this pact. The American attempt to colonise the region effectively led to the “Moro rebellion”. The war resulted in most tragic events and immense human losses. In 1915, a new agreement was signed. Actually Jamal ul-Kiram II was forced by the American governor Frank W. Carpenter to resign the lion’s share of his powers and prerogatives in the USA’s favour, and to accept the direct American administration in Sulu. However, contrary to what was proudly announced by Carpenter, the pact did not deprive the Sultan of all his temporal powers. It should be understood that Carpenter, an able and non-hostile administrator, was opposed in his essentially peaceful plans by many war-minded officials, and in the dispute with them he had many reasons to exaggerate the new pact’s significance. The Sultan’s religious role was confirmed, not affected, by the pact.

The reign of Jamal ul-Kiram II continued under both American and Filipino government until his death in 1936, when Manila decided to ignore the existence of the Sultanate altogether, and denied to express any recognition, let alone any patronage, as to the new Sultan, Muwallil Wasit II. This imprudent governmental decision was followed by the latter’s murder, and resulted in further political entropy and a new dynastic schism.

During the II World War, there were two active claimants to the Kingship, one being supported by Japan and another opposing the Japanese occupation; none of them was of the Kiram Royal stem. The latter was however restored in the person of the then legitimist heir, Mohammad Esmail Kiram I (Muwallil Wasit’s son), in 19505.

This restoration was formally recognised by the Republic of the Philippines in 1962 and again in 1972, as the government in Manila gradually became interested in the Sulu affairs, partly due to the North Borneo dispute, and partly because of the growing radical attitude in the authonomist and separatist Moro movements, to which the traditional monarchist establishment seemed (and largely was and still is) a plausible alternative.

IV. The North Borneo problem

In 1675, the throne of the neighbouring realm of Brunei was disputed and the Sultan of Sulu was asked to settle the conflict as an arbiter; when the negotiations were proved useless, the Sultan used his army in favour of one of the claimants, helped to stop the civil war and was generously rewarded with the northern part of the Kalimantan (Borneo). It was in 1878 that the then Sultan, Jamal ul-A’Lam, looking for a political balance in the region, granted this part of the Sultanate on lease to Europeans. With time, North Borneo became a British crown colony and then was incorporated into Malaysia as the province of Sabah. The Sultan remained the de jure supreme sovereign of North Borneo and continued to receive the annual fee as established by the initial agreement. It worth mentioning that the Sultan’s rights were confirmed by judicial and governmental acts in Sabah and Malaysia, and that neither Bates Agreement nor Carpenter Agreement affected these royal rights in any way, because the US explicitly declined from interfering into this delicate matter. Numerous influential Filipino politicians, to the opposite, considered North Borneo a part of the Sultanate of Sulu and thus a dominion of the Philippines. Thus the claim to Sabah appeared depending on the Sultanate’s existence. To obtain the formal recognition of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu by Manila (which implied a chance to reestablish the Tausug autonomy), Sultan Esmail twice (in 1962 and in 1969) signed acts of cession of North Borneo to the Republic, but as the latter failed to implement the practical provisions of these acts, such as to claim the province effectively, both these acts appeared void. The North Borneo case remains a complicated legal as well as political problem. Malaysia continues to pay the rent to this day.

V. The current state of the Kingdom

In 1974, Sultan Esmail died and was duly succeeded by his son and heir Mohammad Mahakuttah Kiram6. The accession of the new Sultan was solemnly recognised by the Filipino President, under whose act Manila acknowledged not only the personal status of the Sultan-King but also the formation of the government of Sulu. Presidential representatives attended the coronation of HM Sultan Mahakutta on 24th May 1974. On this occasion, Mahacutta’s son and heir HRH Datu Muedzul-Lail was installed (and formally recognized by the Filipino state) as the Raja Muda (Prince Royal and heir apparent).

Sultan Mahakutta passed away in 1986 when the political situation in the Philippines was profoundly different; the power passed from the dictator Ferdinand Marcos to an experiment-minded leader, Corazón Aquino, the perspectives were uncertain, and the political instability in the Moroland was growing dramatically. Manila declined from supporting the new head of the house. Young Raja Muda Muedzul-Lail was advised neither to arrange a coronation without recognition from Manila, nor to throw the Crown into the struggle between the secessionists and the adherents of the Republic. Therefore Muedzul-Lail preferred to remain, temporarily, a Raja Muda and HRH instead of assuming the title and style of the Sultan-King, although it was understood that this decision, according to the Sulu customs, deprived him neither from the headship of the Sultanate nor from the ruler’s prerogatives.

Due to the turbulent political circumstances, the traditional structure of the Sultanate was largely destabilised and numerous pretenders started claiming the throne, to fill the imaginary gap in the leadership. Several coronations were masqueraded. Even Muedzul-Lail”s uncle Datu Fouad, on being appointed by his nephew a viceroy for North Borneo, failed to stand a temptation and used this opportunity to proclaim himself a Sultan both in Sulu and, separately, in Sabah. All these frenetic attempts were, and are, in a striking contrast with Raja Muda Muedzul-Lail’s quietly consistent realistic attitude and his policy of gradual restoration. Currently the Raja Muda operates as a full-scale ruler, assisted by the traditional assembly of the nobility and the notables, the Ruma Bichara.

The heir to the Sultanate is the Raja Muda’s elder son Mohammad Ehsn S. Kiram, who currently enjoys the title of Maharaja Adinda (“the second heir” or “the heir to the heir”). The Raja Muda’s five sons guarantee the firm Kiram succession.

To unite the compatriots, that is, the traditional aristocracy and the commoners alike, the Tausugs as well as the non-Tausug settlers; to gain the recognition of the Philippine Republic for the traditional social practices of the Tausug nation, for which the current Filipino law offers an opportunity; to revive the constructive relations with other Malay and non-Malay sovereign houses: these and other similar tasks, being integral parts of the Raja Muda’s agenda, cannot be accomplished without caution and patience, but also without bold initiatives. The current royal honours policy of the Raja Muda, as an example of such an initiative, will be discussed in a separate paper.

VI. The symbols of the Kingdom

Heraldry makes a fine dessert when not served as a main course. To conclude the survey, it will be useful to pay attention to the nation’s flag and insignia armorial. Since the times immemorial, the Tausugs used various flags to mark the rulers’ residences and vessels. From this practice emerged gradually the constant use of the Royal flags in the 19th century. It is likely that they were originally white and that the further predominance of the red colour was due to the influence of the battle banners. The elaborate ornamental image typical for the flags and banners of the time could, as some authors suggest, originate as the stylised image of the entrance into the Royal capital (Jolo) or the residence (the palace/Astana); but it came to denote the Gateway to Mecca. Another element regularly met with on the old flags is the Zulphiqar, the sacred double sword, as the symbol of the superior authority of the Sultan. A double stripe, usually of blue and white, often appeared at the hoist. Under the American protectorate and occupation, the Sultan was asked to stop using the old flag; and a new, USA-inspired flag was introduced, also red, but this time with a blue canton bearing stars (to denote the five parts of the Sultanate). The traditional Tausug weapons (a kris and a spear, the allegorical composition mentioned above, from time to time completed with a barung) were represented on the red background of this new flag and so was the crescent symbol of Islam, sometimes replaced with a white roundel, representing a celestial body or a pearl, if not both. Several attempts were made to create a correct coat of arms for the Sultanate but for long the heraldic symbols in use remained rather imitative and failed to reflect the authentic tradition of Sulu.

It was in 2011 that HRH the Raja Muda, assisted by the Ruma Bichara, legally established the new arms and flag of Sulu.

The flag reflects different historical levels of the Sultanate’s symbolism, displaying the highly stylised Gateway of Mecca symbolically topped by Zulphiqar over the kris-and-spear national badge. Both the double stripe (of the Royal livery colours, blue and white) and the canton (although with a new composition) are kept, and so is the pearl. The arms are tripartite and show the Meccan Gateway with Zulphiqar (for the Sultanate of Sulu), the Islamic crescent-and-star distinctively completed with the flame of holiness (for the Hashemite descent and the spiritual authority), and an umbrella-topped Kalimantan roofed boat which symbol is borne in the Royal right of North Borneo. On the least splendid occasions, the central part may be borne alone. The arms are ensigned with the heraldic Royal crown of Sulu. The supporters are the two sea-tigers holding the kris and the spear. The full achievement includes also the Royal ceremonial cap, the crest on a wreath, the collar of the house order, the distinctive Royal robe, the state gonfanon, a slogan and a motto. The national arms constitute also the Royal arms of Sulu, and are currently borne by HRH the Raja Muda.

http://www.royalsultanateofsulu.org/#!history

5. KHAS : KENYATAAN RASMI SULTAN SULU

http://www.royalsultanateofsulu.org/#!

Under the headship of Ampun Sultan Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram of Sulu, 35th Sultan of Sulu

Statement: Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram, 35th Sultan of Sulu, son of Mahakuttah Kiram (last recognised Sultan of Sulu by Philippine government under Presidential Memorandum Order 427 issued in 1974 by President of the Philippines), 34th Sultan of Sulu, grandson of Esmail Kiram I, 33rd Sultan of Sulu on the situation in Lahad Datu, Sabah, March 8, 2013.

Since 11th of February, after my uncle, Jamalul Kiram III, and his followers clashed with Malaysian authorities in Lahad Datu, Sabah my primary concern has been my fellow countryman safety and to resolve the incident peacefully. I have continuously urged all parties put end to the violence in Sabah and encouraging dialogue for a peaceful resolution of the situation.

I am saddened to hear that on 7 March 2013, the Malaysian Foreign Ministry issued a statement where it said it considers my uncle forces as a group of terrorists "following their atrocities and brutalities committed in the killing of Malaysia’s security personnel.", therefore I have been in touch with the Director for Southeast Asia I, Office of Asian and Pacific Affairs, Department of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Philippines, and offered myself to become independent negotiator as Lahad Datu standoff must end now. We know that it has already spread from Lahad Datu to Semporna, Kunak, Tanduo and to Tawau in Eastern Sabah.

6. KENYATAAN PERTUBUHAN BANGSA BANGSA BERSATU (PBB)

http://unyearbook.un.org/1963YUN/1963_P1_SEC1_CH3.pdf (Page 42 & 42)

THE QUESTION OF MALAYSIA

EXCHANGE OF CORRESPONDENCE

The proposal for the formation of Malaysia

was first made by the Prime Minister of the

Federation of Malaya in May 1961, and a

Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Committee

was established at a regional meeting of the

Commonwealth Parliamentary Association in

July of the same year. Following a report by a

Commission of Enquiry (the Cobbold Commission), which had conducted meetings in

Sarawak and North Borneo from February to

April 1962, the Governments of the United

Kingdom and the Federation of Malaya issued a joint statement, on 1 August 1962, that

in principle the Federation of Malaysia should

be established by 31 August 1963. A formal

agreement was prepared and signed in London

on 9 July 1963 on behalf of the Governments

concerned (the Federation of Malaya, North

Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore).

On 5 August 1963, following a six-day meeting in Manila of the Heads of Government of

the Federation of Malaya, Indonesia and the

Philippines, the Foreign Ministers of these three

States cabled the Secretary-General of the

United Nations, requesting him to send working teams to Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak in order to ascertain the wishes of these

peoples with respect to the proposed Federation. The three Governments would similarly

send observers to the two territories to witness

the investigations of the working teams and the

Federation of Malaya would do its best to ensure the co-operation of the British Government and of the Governments of Sabah and

Sarawak.

The terms of reference of the request to the

Secretary-General were set out in paragraph 4

of the Manila Joint Statement as quoted in the

request addressed to the Secretary-General by

the three Foreign Ministers:

The Secretary-General or his representative should

ascertain, prior to the establishment of the Federation

of Malaysia, the wishes of the people of Sabah

(North Borneo) and Sarawak within the context of

General Assembly resolution 1541(XV), Principle IX

of the Annex, by a fresh approach, which in the

opinion of the Secretary-General is necessary to ensure complete compliance with the principle of selfdetermination within the requirements embodied in

Principle IX, taking into consideration: (1) The

recent elections in Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak but nevertheless further examining, verifying

and satisfying himself as to whether: (a) Malaysia

was a major issue if not the major issue; (b) electoral

registers were properly compiled; (c) elections were

free and there was no coercion; and (d) votes were

properly polled and properly counted; and (2) the

wishes of those who, being qualified to vote, would

have exercised their right of self-determination in the

recent elections had it not been for their detention

for political activities, imprisonment for political offences or absence from Sabah (North Borneo) or

Sarawak.

(Principle IX of the Annex of General Assembly resolution 1541(XV) of 15 December

1960 provided that a non-self-governing territory integrating with an independent State

should have attained an advanced stage of selfgovernment with free political institutions. The

same principle lays down that integration should

be the result of the freely expressed wishes of

the territory's peoples, expressed through informed and democratic processes, impartially

conducted and based on universal adult suffrage.1

)

In his reply to the three Foreign Ministers

on 8 August, the Secretary-General made it

clear that he could undertake the task proposed

only with the consent of the United Kingdom.

He believed that the task could be carried out

by his representative and proposed to set up two

working teams—one to work in Sarawak and the

other in Borneo—under the over-all supervision

of his representative. The Secretary-General

emphasized that the working teams would be

responsible directly and exclusively to him and,

on the completion of their task, would report

through his representative to the SecretaryGeneral himself who, on the basis of this report, would communicate his final conclusions

to the three Governments and the Government

of the United Kingdom. It was the SecretaryGeneral's understanding that neither the report

of his representative nor his conclusions would

be subject in any way to ratification or confirmation by any of the Governments concerned.

1

See Y.U.N., 1960, pp. 509-10.42 POLITICAL AND SECURITY QUESTIONS

REPORT OF

UNITED NATIONS MISSION

On 12 August, the Secretary-General announced the assignment of eight members of the

Secretariat, headed by Laurence V. Michelmore as his representative, to serve on the

United Nations Malaysia Mission. The Mission left New York on 13 August 1963 and arrived in Kuching, Sarawak, at noon on 16

August.

The Mission was divided into two

teams, each comprising four officers, one to

remain in Sarawak and the other to work in

Sabah (North Borneo). Both teams remained

until 5 September. Observers from the Federation of Malaya and the United Kingdom were

present throughout all of the hearings conducted by the Mission. Observers from the Republic of Indonesia and from the Philippines

arrived only on 1 September and attended

hearings in the two territories on 2, 3 and 4

September.

On 14 September, the final conclusions of

the Secretary-General with regard to Malaysia

were made public. These conclusions were based

upon a report submitted to the Secretary-General by the Mission. This report stated that it

had been understood that by the "fresh approach" mentioned in the terms of reference

established in the request to the Secretary-General, a referendum, or plebiscite, was not contemplated. The Mission had considered that it

would be meaningful to make a "fresh approach" by arranging consultations with the

population through elected representatives, leaders and the representatives of political parties

as well as non-political groups, and with any

other persons showing interest in setting forth

their views. During the Mission's visits to various parts of the two territories, it had been

possible to consult with almost all of the "grass

roots" elected representatives. Consultations

were also held with national and local representatives of each of the major political groups

and with national and local representatives of

ethnic, religious, social and other groups, as

well as organizations of businessmen, employers and workers in various communities and

social groups.

As far as the specific questions which the

Secretary-General was asked to take into consideration were concerned, the members of the

Mission concluded, after evaluating the evidence available to them, that: (a) in the recent elections Malaysia was a major issue

throughout both territories and the vast majority of the electorate understood the significance

of this; (b) electoral registers were properly

compiled; (c) the elections were freely and impartially conducted with active and vigorous

campaigning by groups advocating divergent

courses of action; and (d) the votes were properly polled and counted; the number of instances where irregularities were alleged seemed

within the normal expectancy of well-ordered

elections.

The Mission came to the conclusion that the

number of persons of voting age detained for

political offences or absent from the territories

when voting took place was not sufficient to

have affected the result.

The Mission also gave careful thought to the

reference in the request to the Secretary-General that "he ascertain prior to the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia the wishes

of the people of Sabah (North Borneo) and

Sarawak within the context of General Assembly resolution 1541 (XV), Principle IX of the

Annex." After considering the constitutional,

electoral and legislative arrangements in Sarawak and Sabah (North Borneo), the Mission

came to the conclusion that the territories had

"attained an advanced stage of self-government

with free political institutions so that its people

would have the capacity to make a responsible

choice through informed democratic processes."

Self-government had been further advanced in

both territories by the declaration of the respective Governors that, as from 31 August

1963, they would accept unreservedly and automatically the advice of the respective Chief

Ministers on all matters within the competence

of the State and for which portfolios had been

allocated to Ministers. The Mission was further of the opinion that the participation of the

two territories in the proposed Federation, having been approved by their legislative bodies,

as well as by a large majority of the people

through free and impartially conducted elections in which the question of Malaysia was a

major issue and fully appreciated as such by

the electorate, could be regarded as the "result

of the freely expressed wishes of the territory'sQUESTIONS CONCERNING

peoples acting with full knowledge of the

change in their status, their wishes having been

expressed through informed and democratic

processes, impartially conducted and based on

universal adult suffrage."

CONCLUSIONS OF

SECRETARY-GENERAL

In submitting his own conclusions, the Secretary-General said he had given consideration

to the circumstances in which the proposals for

the Federation of Malaysia had been developed

and discussed, and the possibility that people

progressing through the stages of self-government might be less able to consider in an entirely free context the implications of such

changes in their status than a society which

had already experienced full self-government

and determination of its own affairs. He had

also been aware, he said, that the peoples of

the territories concerned were still striving for

a more adequate level of educational development. Taking into account the framework within which the Mission's task had been performed,

he had come to the conclusion that the majority of the peoples of Sabah (North Borneo)

and of Sarawak had given serious and thoughtful consideration to their future and to the

implications for them of participation in a Federation of Malaysia. He believed that the majority of them had concluded that they wished

to bring their dependent status to an end and

to realize their independence through freely

chosen association with other peoples in their

region with whom they felt ties of ethnic association, heritage, language, religion, culture,

economic relationship, and ideals and objectives. Not all of those considerations were present in equal weight in all minds, but it was

his conclusion that the majority of the peoples

of the two territories wished to engage, with

the peoples of the Federation of Malaya and

Singapore, in an enlarged Federation of Malaysia through which they could strive together

to realize the fulfilment of their destiny.

The Secretary-General referred to the fundamental agreement of the three participating

ASIA AND THE FAR EAST 43

Governments and the statement by the Republic

of Indonesia and the Republic of the Philippines

that they would welcome the formation of the

Federation of Malaysia provided that the support of the people of the territories was ascertained by him, and that, in his opinion, complete compliance with the principle of selfdetermination within the requirements of General Assembly resolution 1541(XV), Principle

IX of the Annex, had been ensured. He had

reached the conclusion, based on the findings

of the Mission that on both of those counts

there was no doubt about the wishes of a sizeable majority of the people of those territories

to join in the Federation of Malaysia

.

SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS

The Federation of Malaysia was proclaimed

on 16 September 1963. On 17 September, at

the opening meeting of the General Assembly's

eighteenth session, the representative of Indonesia took exception to the fact that the seat of

the Federation of Malaya in the Assembly Hall

was being occupied by the representative of the

Federation of Malaysia. Indonesia had withheld recognition of the Federation of Malaysia

for very serious reasons and reserved the right

to clarify its position on the question of Malaysia at a later stage

Recognition of Malaysia was also withheld by

the Republic of the Philippines. During the

general debate at the eighteenth session, both

Indonesia and the Philippines expressed their

reservations about the findings of the United

Nations Malaysia Mission. The representatives

of the United Kingdom and of the Federation

of Malaysia replied to the Indonesian and Philippine charges and upheld the findings of the

United Nations Malaysian Mission

.

On 12 December, during the meeting of the

Credentials Committee, the USSR supported

the Indonesian position with regard to the seating of the representatives of Malaysia in the

General Assembly. A proposal by the Chairman of the Credentials Committee that the

Committee find the credentials of all representatives in order was nonetheless approved.

On 12 December, during the meeting of the

Credentials Committee, the USSR supported

the Indonesian position with regard to the seating of the representatives of Malaysia in the

General Assembly. A proposal by the Chairman of the Credentials Committee that the

Committee find the credentials of all representatives in order was nonetheless approved.

Refer also to :

http://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20550/volume-550-I-8029-English.pdf

Also :

http://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20608/volume-608-I-8809-English.pdf

AKAN BERSAMBUNG...............PART 2 DAN SETERUSNYA

ANALISA DAN KAJIAN ADMIN

BLOG ABG

BLOG ABG

No comments:

Post a Comment